Marcel Proust: À la recherche du temps perdu

Du côté de chez Swann (1913)

Excerpt (French and English) from Part One: Combray

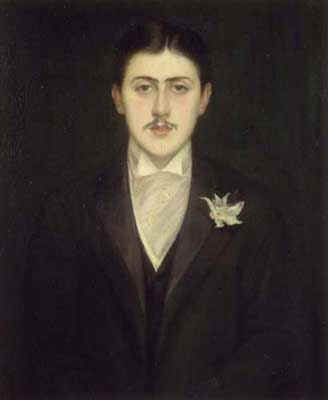

Jacques-Emile Blanche: Portrait de Marcel Proust (1892)

Musée d'Orsay, Paris - France

[...] Il y avait déjà bien des années que, de Combray, tout ce qui n’était pas le théâtre et la drame de mon coucher, n’existait plus pour moi, quand un jour d’hiver, comme je rentrais à la maison, ma mère, voyant que j’avais froid, me proposa de me faire prendre, contre mon habitude, un peu de thé. Je refusai d’abord et, je ne sais pourquoi, me ravisai. Elle envoya chercher un de ces gâteaux courts et dodus appelés Petites Madeleines qui semblaent avoir été moulés dans la valve rainurée d’une coquille de Saint-Jacques. Et bientôt, machinalement, accablé par la morne journée et la perspective d’un triste lendemain, je portai à mes lèvres une cuillerée du thé où j’avais laissé s’amollir un morceau de madeleine. Mais à l’instant même où la gorgée mêlée des miettes du gâteau toucha mon palais, je tressaillis, attentif à ce qui se passait d’extraordinaire en moi. Un plaisir délicieux m’avait envahi, isolé, sans la notion de sa cause. Il m’avait aussitôt rendu les vicissitudes de la vie indifférentes, ses désastres inoffensifs, sa brièveté illusoire, de la même façon qu’opère l’amour, en me remplissant d’une essence précieuse: ou plutôt cette essence n’était pas en moi, elle était moi. J’avais cessé de me sentire médiocre, contingent, mortel. D’où avait pu me venir cette puissante joie? Je sentais q’elle était liée au goût du thé et du gâteau, mais qu’elle le dépassait infiniment, ne devait pas être de même nature. D’où venait-elle? Que signifiait-elle? Où l’appréhender? Je bois une seconde gorgée où je ne trouve rien de plus que dans la première, une troisième qui m’apporte un peu moins que la seconde. Il est temps que je m’arrête, la vertu du breuvage semble diminuer. Il est clair que la vérité que je cherche n’est pas en lui, mais en moi. Il l’y a éveillée, mais ne la connaît pas, et ne peut que répéter indéfiniment, avec de moins en moins de force, ce même témoignage que je ne sais pas interpréter et que je veux au moins pouvoir lui redemander et retrouver intact, à ma disposition, tout à l’heure, pour un éclaircissement décisif. Je pose la tasse et me tourne vers mon esprit. C’est à lui de trouver la vérité. Mais comment? Grave incertitude, toutes les fois que l’esprit se sent dépassé par lui-même; quand lui, le chercheur, est tout ensemble le pays obscur où il doit chercher et où tout son bagage ne lui sera de rien. Chercher? pas seulement: créer. Il est en face de quelque chose qui n’est pas encore et que seul il peut réaliser, puis faire entrer dans sa lumière.

Et je recommence à me demander quel pouvait être cet état inconnu, qui n’apportait aucune preuve logique, mais l’evidence de sa félicité, de sa réalité devant laquelle les autres s’évanouissaient. Je veux essayer de le faire réapparaître. Je rétrograde par la pensée au moment où je pris la première cuillerée de thé. Je retrouve le même état, sans une clarté nouvelle. Je demande à mon esprit un effort de plus, de ramener encore une fois la sensation qui s’enfuit. Et pour que rien ne brise l’élan dont il va tâcher de la ressaisir, j’écarte tout obstacle, toute idée étrangère, j’abrite mes oreilles et mon attention contre les bruits de la chambre voisine. Mais sentant mon esprit qui se fatigue sans réussir, je le force au contraire à prendre cette distraction que je lui refusais, à penser à autre chose, à se refaire avant une tentative suprême. Puis une deuxième fois, je fais le vide devant lui, je remets en face de lui la saveur encore récente de cette première gorgée et je sens tressaillir en moi quelque chose qui se déplace, voudrait s’élever, quelque chose qu’on aurait désancré, à une grande profondeur; je ne sais ce que c’est, mais cela monte lentement; j’éprouve la résistance et j’entends la rumeur des distances traversées.

Certes, ce qui palpite ainsi au fond de moi, ce doit être l’image, le souvenir visuel, qui, lié à cette saveur, tente de la suivre jusqu’à moi. Mais il se débat trop loin, trop confusément; à peine si je perçois le reflet neutre où se confond l’insaisissable tourbillon des couleurs remuées; mais je ne puis distinguer la forme, lui demander comme au seul interprète possible, de me traduire le témoignage de sa contemporaine, de son inséparable compagne, la saveur, lui demander de m’apprendre de quelle circonstance particulière, de quelle époque du passé il s’agit.

Arrivera-t-il jusqu’à la surface de ma claire conscience, ce souvenir, l’instant ancien que l’attraction d’un instant identique est venue de si loin solliciter, émouvoir, soulever tout au fond de moi? Je ne sais. Maintenant je ne sens plus rien, il est arrêté, redescendu peut-être; qui sait s’il remontera jamais de sa nuit? Dix fois il me faut recommencer, me pencher vers lui. Et chaque fois la lâcheté qui nous détourne de toute tâche difficile, de toute œuvre important, m’a conseillé de laisser cela, de boire mon thé en pensant simplement à mes ennuis d’aujourd’hui, à mes désirs de demain qui se laissent remâcher sans peine.

Et tout d’un coup le souvenir m’est apparu. Ce goût celui du petit morceau de madeleine que le dimanche matin à Combray (parce que ce jour-là je ne sortais pas avant l’heure de la messe), quand j’allais lui dire bonjour dans sa chambre, ma tante Léonie m’offrait après l’avoir trempé dans son infusion de thé ou de tilleul. La vue de la petite madeleine ne m’avait rien rappelé avant que je n’y eusse goûté; peut-être parce que, en ayant souvent aperçu depuis, sans en manger, sur les tablettes des pâtissiers, leu image avait quitté ces jours de Combray pour se lier à d’autres plus récents; peut-être parce que de ces souvenirs abandonnés si longtemps hors de la mémoire, rien ne survivait, tout s’était désagrégé; les formes,—et celle aussi du petit coquillage de pâtisserie, si grassement sensuel, sous son plissage sévère et dévot—s’étaient abolies, ou, ensommeillées, avaient perdu la force d’expansion qui leur eût permis de rejoindre la conscience. Mais, quand d’un passé ancien rien ne subsiste, après la mort des êtres, après la destruction des choses, seules, plus frêles mais plus vivaces, plus immatérielles, plus persistantes, plus fidèles, l’odeur et la saveur restent encore longtemps, comme des âmes, à se rappeler, à attendre, à espérer, sur la ruine de tout le reste, à porter sans fléchir, sur leur gouttelette presque impalpable, l’édifice immense du souvenir.

Et dès que j’eus reconnu le goût du morceau de madeleine trempé dans le tilleul que me donnait ma tante (quoique je ne susse pas encore et dusse remettre à bien plus tard de découvrir pourquoi ce souvenir me rendait si heureux), aussitôt la vieille maison grise sur la rue, où était sa chambre, vint comme un décor de théâtre s’appliquer au petit pavillon, donnant sur le jardin, qu’on avait construit pour mes parents sur ses derrières (ce pan tronqué que seul j’avais revu jusque-là); et avec la maison, la ville, la Place où on m’envoyait avant déjeuner, les rues où j’allais faire des courses depuis le matin jusqu’au soir et par tous les temps, les chemins qu’on prenait si le temps était beau. Et comme dans ce jeu où les Japonais s’amusent à tremper dans un bol de porcelaine rempli d’eau, de petits morceaux de papier jusque-là indistincts qui, à peine y sont-ils plongés s’étirent, se contournent, se colorent, se différencient, deviennent des fleurs, des maisons, des personnages consistants et reconnaissables, de même maintenant toutes les fleurs de notre jardin et celles du parc de M. Swann, et les nymphéas de la Vivonne, et les bonnes gens du village et leurs petits logis et l’église et tout Combray et ses environs, tout cela que prend forme et solidité, est sorti, ville et jardins, de ma tasse de thé.

(In Search of Lost Time: Swann's Way)

[...] Many years had elapsed during which nothing of Combray, save what was comprised in the theatre and the drama of my going to bed there, had any existence for me, when one day in winter, on my return home, my mother, seeing that I was cold, offered me some tea, a thing I did not ordinarily take. I declined at first, and then, for no particular reason, changed my mind. She sent for one of those squat, plump little cakes called "petites madeleines," which look as though they had been moulded in the fluted valve of a scallop shell. And soon, mechanically, dispirited after a dreary day with the prospect of a depressing morrow, I raised to my lips a spoonful of the tea in which I had soaked a morsel of the cake. No sooner had the warm liquid mixed with the crumbs touched my palate than a shudder ran through me and I stopped, intent upon the extraordinary thing that was happening to me. An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory - this new sensation having had on me the effect which love has of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me it was me. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I sensed that it was connected with the taste of the tea and the cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could, no, indeed, be of the same nature. Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it?

I drink a second mouthful, in which I find nothing more than in the first, then a third, which gives me rather less than the second. It is time to stop; the potion is losing it magic. It is plain that the truth I am seeking lies not in the cup but in myself. The drink has called it into being, but does not know it, and can only repeat indefinitely, with a progressive diminution of strength, the same message which I cannot interpret, though I hope at least to be able to call it forth again and to find it there presently, intact and at my disposal, for my final enlightenment. I put down the cup and examine my own mind. It alone can discover the truth. But how: What an abyss of uncertainty, whenever the mind feels overtaken by itself; when it, the seeker, is at the same time the dark region through which it must go seeking and where all its equipment will avail it nothing. Seek? More than that: create. It is face to face with something which does not yet exist, to which it alone can give reality and substance, which it alone can bring into the light of day.

And I begin to ask myself what it could have been, this unremembered state which brought with it no logical proof, but the indisputable evidence, of its felicity, its reality, and in whose presence other states of consciousness melted and vanished. I decide to attempt to make it reappear. I retrace my thoughts to the moment at which I drank the first spoonful of tea. I rediscover the same state, illuminated by no fresh light. I ask my mind to make one further effort, to bring back once more the fleeting sensation. And so that nothing may interrupt it in its course I shut out every obstacle, every extraneous idea, I stop my ears and inhibit all attention against the sound from the next room. And then, feeling that my mind is tiring itself without having any success to report, I compel it for a change to enjoy the distraction which I have just denied it, to think of other things, to rest refresh itself before making a final effort. And then for the second time I clear an empty space in front of it; I place in position before my mind's eye the still recent taste of that first mouthful, and I feel something start within me, something that leaves its resting-place and attempts to rise, something that has been embedded like an anchor at a great depth; I do not know yet what it is, but I can feel it mounting slowly; I can measure the resistance, I can hear the echo of great spaces traversed.

Undoubtedly what is thus palpitating in the depths of my being must be the image, the visual memory which, being linked to that taste, is trying to follow it into my conscious mind. But its struggles are too far off, too confused and chaotic; scarcely can I perceive the neutral glow into which the elusive whirling medley of stirred-up colours is fused, and I cannot distinguish its form, cannot invite it, as the one possible interpreter, to translate for me the evidence of its contemporary, its inseparable paramour, the taste, cannot ask it to inform me what special circumstance is in question, from what period in my past life.

Will it ultimately reach the clear surface of my consciousness, this memory, this old, dead moment which the magnetism of an identical moment has traveled so far to importune, to disturb, to raise up out of the very depths of my being? I cannot tell. Now I feel nothing; it has stopped, has perhaps sunk back into its darkness, from which who can say whether it will ever rise again? Ten times over I must essay the task, must lean down over the abyss. And each time the cowardice that deters us from every difficult task, every important enterprise, has urged me to leave the thing alone, to drink my tea and to think merely of the worries of to-day and my hopes for to-morrow, which can be brooded over painlessly.

And suddenly the memory revealed itself. The taste was that of the little piece of madeleine which on Sunday mornings at Combray (because on those mornings I did not go out before mass), when I went to say good morning to her in her bedroom , my aunt Léonie used to give me, dipping it first in her own cup of tea or tisane. The sight of the little madeleine had recalled nothing to my mind before I tasted it; perhaps because I had so often seen such things in the meantime, without tasting them, on the trays in pastry-cooks' windows, that their image had dissociated itself from those Combray days to take its place among others more recent; perhaps because of those memories, so long abandoned and put out of mind, nothing now survived, everything was scattered; the shapes of things, including that of the little scallop-shell of pastry, so richly sensual under its severe, religious folds, were either obliterated or had been so long dormant as to have lost the power of expansion which would have allowed them to resume their place in my consciousness. But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, taste and smell alone, more fragile but more enduring, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, remain poised a long time, like souls, remembering, waiting, hoping, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unflinchingly, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection.

And as soon as I had recognized the taste of the piece of madeleine soaked in her decoction of lime-blossom which my aunt used to give me (although I did not yet know and must long postpone the discovery of why this memory made me so happy) immediately the old grey house upon the street, where her room was, rose up like a stage set to attach itself to the little pavilion opening on to the garden which had been built out behind it for my parents (the isolated segment which until that moment had been all that I could see); and with the house the town, from morning to night and in all weathers, the Square where I used to be sent before lunch, the streets along which I used to run errands, the country roads we took when it was fine. And as in the game wherein the Japanese amuse themselves by filling a porcelain bowl with water and steeping in it little pieces of paper which until then are without character or form, but, the moment they become wet, stretch and twist and take on colour and distinctive shape, become flowers or houses or people, solid and recognizable, so in that moment all the flowers in our garden and in M. Swann's park, and the water-lilies on the Vivonne and the good folk of the village and their little dwellings and the parish church and the whole of Combray and its surroundings, taking shape and solidity, sprang into being, town and gardens alike, from my cup of tea.

Translation by C.K. Scott Moncrieff (1922)

source text: Project Gutenberg

Release Date: May, 2001 [EBook #2650]

translation: Project Gutenberg

Release Date: December, 2004 [EBook #7178]